Free to Serve

If you think economists rule the world, look no further than a policy directly affecting a quarter of U.S. workers.

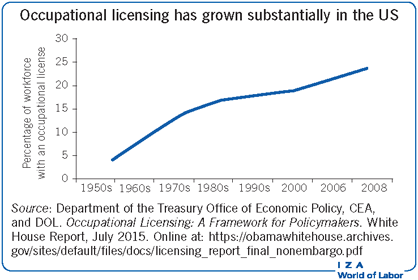

It’s a policy about which nearly all economists express serious doubts. Occupational licenses stipulate that a would-be seller must pass exams, pay fees, and/or get specialized training before selling. Sellers in these industries must get permission before they can serve you. They’re not free to serve.

Consider what happens to workers and customers when public policy limits the number of people who can supply certain goods and services. Workers who get the license earn higher wages when the government restricts entry. However, consumers (also workers!) pay higher prices, and employers (including workers who own stock through retirement funds) pay more. Workers who, for whatever reason, don’t get the license may see their incomes fall as they shift to other occupations.

Consider something high stakes: medicine. Who does the occupational licensure of doctors and other medical professionals protect? Those degrees and certifications they often display on their waiting room walls? Aren’t these designed to protect patients and ensure high-quality care?

Not really.

Economics suggests an answer that you might not expect: Medical licensing protects the incomes of doctors and other medical professionals.

Here are a few findings that have repeatedly emerged from decades of research. First, consumers rarely lobby for tighter licensing restrictions, but licensed group members do. A famous instance comes from the American Medical Association (AMA). When Jewish doctors fleeing the Nazis immigrated to the United States, the AMA scrambled to change the rules. To practice medicine in America, one now had to be a U.S. citizen. What U.S. citizenship has to do with one’s ability to heal the human body successfully is lost on us.

Second, licensure boards tend to be filled with practitioners. And they have every incentive to propose regulations that benefit their industry friends – colleagues to whom they will often return after a stint on the regulatory board. In many other instances, board members practice while serving on the board.

Third, despite widespread licensing in medicine and pharmacy, iatrogenic disorders, problems caused by the practice of medicine itself, are among the leading causes of death in the United States. In other words, it’s not as if the licensing status quo has yielded a consumer utopia. In many cases, licensing boards hesitate to strip a practitioner of his credentials. Once again, we must ask: Who do the licensing boards serve? Producers or consumers?

Fourth, licensing restricts the supply of sellers, raising the price of their services. For instance, licensing means opticians earn .3-.5 percent more every year. Because of the law of demand, people will buy fewer opticians’ services. Some people who might have successfully sought treatment for a vision problem now won’t. Others will put off getting new glasses. Are they better off? Are they “protected” by the new licensing requirements?

Some might object that they are willing to pay higher prices for quality assurance. The vast empirical literature on licensing, and particularly its effects on quality, suggests that’s not what we’re getting. Licenses protect existing sellers from potential rivals. And with boards hesitant to discipline existing sellers, quality falls in many markets. The paper referenced in the previous paragraph finds “Little evidence that optician licensing has enhanced the quality of services delivered to consumers.” Overall, meta-analyses of the literature are ambiguous. Some papers find (marginal) improvements in quality. Others, like the one just cited, find marginal decreases, and others find no change in quality. Remember, though: even the papers finding a marginal improvement due to licensing must grapple with the fact that some consumers will go without the good or service at all thanks to its higher price.

But in a world without licensing, couldn’t anyone hang out a shingle and start practicing medicine?

Yes.

And that’s a boon for consumers because markets regulate more effectively than government licensing boards do. The fact that this is everyone’s first objection suggests that most consumers wouldn’t walk into a random storefront and submit themselves to a haircut without doing their homework, much less to brain surgery. And how many people have gotten out of the stylist’s chair and left because they noticed her license was about to expire?

The fact is, all sorts of market institutions arise to supply quality more effectively than government-backed boards. Brands, third-party certifiers (educational institutions, insurers, evaluators), and apprenticeships to reputable sellers are all means of securing quality and competence.

When real harm happens (and upon occasion, it will), the tort system can punish the injurer. Torts are a part of the Common Law legal tradition that emerged in England almost a thousand years ago. When a person brings harm (of certain varieties) on his neighbor, he has committed a tort, can be sued, and penalized.

The tort system provides an incentive to refrain from harm. Second, and overlooked by many non-economists is what happens to someone who has committed a tort. His insurance premiums will increase, making it harder to survive in the market. Repeat offenders will be weeded out altogether. All this is to say that the system isn’t perfect, which makes it just like the system we have now, or just like any other conceivable system. None prevent 100% of harms.